There are careers in Hollywood that unfold in straight, predictable lines. Then there are careers like Douglas Vermeeren’s—full of detours, lateral jumps, reinventions, and an almost stubborn refusal to fit the traditional mold of how a leading man is supposed to arrive. Yet in 2026, the industry finds itself watching Vermeeren with uncommon attention. The Canadian-born actor, stunt performer, producer, television host, entrepreneur, and emerging international presence hasn’t simply joined the conversation—he has become one of its more surprising focal points.

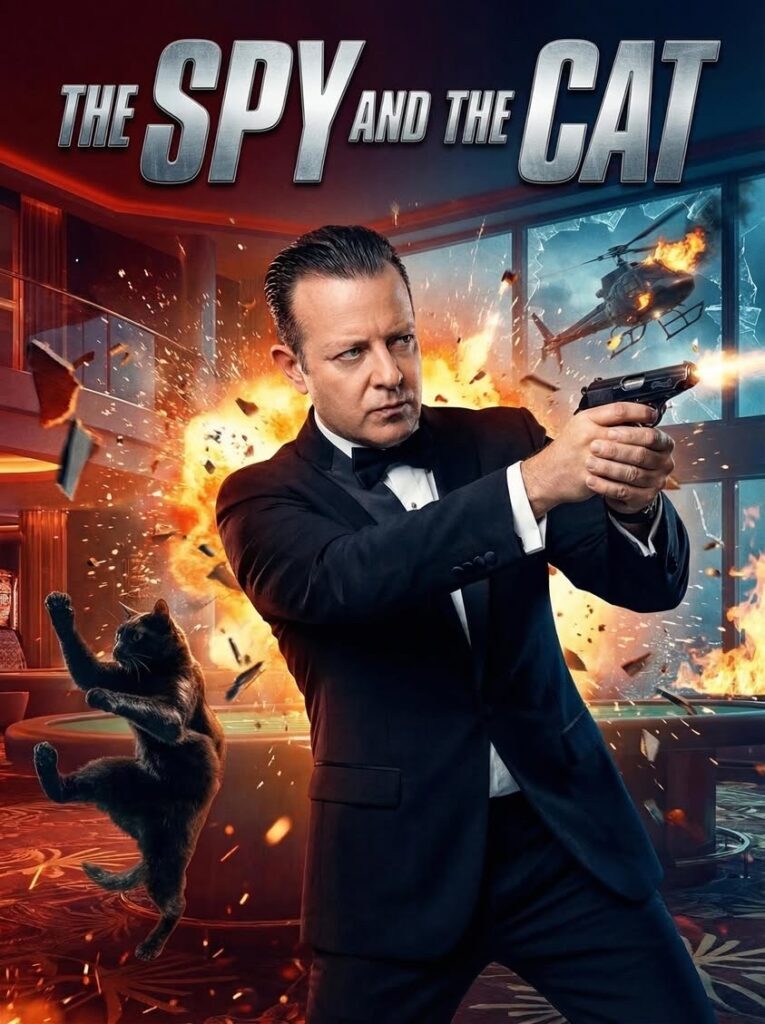

It can be tempting to view Vermeeren through the lens of the present moment: his appearances on magazine covers, red carpets, and festival circuits; his proximity to major stars; the buzz swirling around his upcoming family spy thriller The Spy and The Cat; and the growing speculation that this next turn could be the one that permanently lifts him into the global mainstream. But to understand why this moment matters, it’s worth rewinding to a very different setting far from Cannes, Monaco, and Hollywood—back to a young boy in Canada playing a newspaper kid on a modest local television program.

The role was not glamorous. It paid little. There were no agents, stylists, critics, or paparazzi involved. But something happened on that set. Vermeeren fell in love—not with fame, but with the environment of filmmaking itself. The lights, the cameras, the choreography, the microcosm of creative energy that happens when dozens of professionals collectively decide to create illusion. Where some children dream of seeing themselves in movies, Vermeeren dreamed of simply being near them.

Throughout middle school and high school, he became a regular presence on sets across the region. His solution to balancing education and ambition was pragmatic if not exactly academic: he began skipping classes. By the time he graduated, he had worked as a background performer in more than fifty film and television productions. There were no breakout roles or precocious award nominations attached to those credits—just relentless enthusiasm, a willingness to do the work, and an emerging familiarity with how sets function from the inside out.

The stunt world arrived next. Vermeeren had always been physical. He was a martial artist first, a competitive one with a background in multiple styles of karate and later Brazilian jiu-jitsu, where he went on to win several gold medals in competition. Stunts offered not only a job, but a portal into a world where his physicality and his fascination with cinema could co-exist.

His first major stunt assignment landed him on the set of Kevin Costner’s Western Open Range, a film that featured Costner alongside Robert Duvall, Annette Bening, and Diego Luna. Vermeeren served as a stunt performer and photo double for actor Ian Tracey, a job that involved everything from riding to falls to movement replication. More importantly, it placed him in proximity to Oscar-winning talent and large-scale filmmaking infrastructure.

The summer of Open Range quickly turned into what might be called his Western period. He joined the remake of Monty Walsh, starring Tom Selleck, William Devane, and Robert Carradine, followed by DreamKeeper, where he photo doubled for Scott Grimes. These were not yet roles that would land him on billboards or gossip columns, but they were foundational. They shaped the version of Vermeeren that audiences would later encounter: the actor who prefers to do his own stunts, the performer unafraid of falling off a horse or throwing a punch, and the creative who understands that film is as much about craft as it is about celebrity.

Then, suddenly, the narrative takes a turn. While plenty of actors treat film as a means to express character, Vermeeren turned toward producing titles with social, philosophical, and commercial resonance. He became a key figure in the personal development and law-of-attraction space, producing five of the most prominent films in that world and populating them with the highest-profile names available—Jack Canfield and Mark Victor Hansen of Chicken Soup for the Soul fame; Bob Proctor; Denis Waitley; John Demartini; John Assaraf; Marie Diamond; Joe Vitale; Marci Shimoff; and other thought leaders who helped propel the 2006 hit The Secret into a global cultural phenomenon.

The standout of Vermeeren’s producing catalog became The Opus, which was translated into more than twenty-six languages and distributed worldwide. It was the type of success that reframed him—not merely as a performer, but as an intellectual property generator with reach far beyond his immediate geography. While many actors struggle to find projects, Vermeeren was suddenly creating them.

If one thread in his career highlights his ability to engineer content, another underscores his affinity for audiences. Somewhere between film sets and business ventures, Vermeeren became a television host. In China, he hosted a variety show and recorded English tourism audio guides for many of the country’s key historical sites—projects commissioned through official tourism channels. This unusual assignment, half cultural diplomacy and half entertainment, widened his appeal internationally and placed him in front of millions of listeners who might never have encountered him otherwise.

Back in North America, his television momentum continued. Vermeeren hosted or co-hosted Unexplained Paranormal Files, The Video Games That Changed the World, and The Origin of Monsters, a trio of genre programs that occupy the space between documentary and pop entertainment. They also demonstrated Vermeeren’s eclectic curiosities—technology, mythology, history, folklore, and fringe cultural questions. Few actors have résumés that place them in both a Kevin Costner Western and a paranormal investigation series. Vermeeren seems comfortable in both.

While television expanded his visibility, film deepened his legitimacy. He earned a Best Actor award for his performance as Billy LaChance in Jackknife, which premiered at the TIFF Lightbox—a prestigious venue with no shortage of critical eyes. Later, he won Best Villain for his turn as Hank Winslow in the action thriller Black Creek, a project notable not only for the award but for its ensemble, which featured martial arts legends Cynthia Rothrock, Richard Norton, Keith Cooke, and Patrick Kilpatrick. Vermeeren fit comfortably among them, assisted by his real martial arts background and reputation for doing much of his own stunt work.

Alongside awards came supporting work opposite major talent—Juliette Lewis, Peter Dinklage, Melissa McCarthy, Clive Owen, Dee Wallace, and others—quietly shifting the perception of where he belonged within the industry’s hierarchy. He was no longer merely a background performer, a stunt guy, or a niche producer. He was becoming a legitimate actor in films that mattered.

But if there is a single project that has observers whispering about “breakout moment” potential, it is The Spy and The Cat, a family spy thriller currently in production and generating authentic excitement. It blends humor, action, espionage, and family-friendly spectacle into a narrative cocktail studios adore, and—if early sentiment proves accurate—Vermeeren appears poised to benefit from the exposure. Insiders have noted that the role allows him to draw equally from his physical skills and his comedic instincts, two qualities that are difficult to combine convincingly and even harder to teach. There is a reason audiences love action heroes who know how to wink.

The attention surrounding Vermeeren isn’t confined to screens and sets. Increasingly, he has become a fixture at places where cultural power converges: awards shows, film festivals, and fashion circuits. He has been spotted at the Golden Globes, the Oscars, and is a recognizable regular at the Cannes Film Festival. Unlike the actors who rush through the Riviera as guests, Vermeeren lingers—talking, networking, and slipping into the parties that exist at the high-altitude levels of the industry ecosystem.

His presence in fashion has amplified even faster. He has appeared on the cover of GQ no fewer than four times across different editions, and recently graced the covers of Vogue Monaco and Vanity Fair. The fashion world has always been fond of actors with ambiguous mystique—chiseled enough for editorial spreads, enigmatic enough for cultural fascination. Vermeeren has become catnip for that sensibility.

And yet, privately, he remains private. He does not travel with entourages or issue press statements about his personal life. He was married from 2003 until 2022, his most recent marriage to Holly Jarocki ending quietly and amicably with no children. He is now officially single. Though frequently photographed in the company of models and striking women at industry functions, he rejects the playboy narrative. When asked about romance, Vermeeren describes himself as “hopeful to find [his] soulmate and best friend,” a line that carries a surprising sincerity for someone nicknamed “Cinema’s Bad Boy.”

The nickname, for the record, has more to do with his stunt work and martial arts bravado than scandal. The bad boy descriptor is action-genre shorthand—less tabloid, more Tough Mudder. He is a fighter in real life, trained across multiple disciplines, and decorated in competition. Directors appreciate performers like that. Insurance companies tolerate them. Audiences adore them.

If there is a business mind beneath the artist, it reveals itself through Vermeeren’s entrepreneurial ventures. He invests, develops projects, and quietly builds companies. Sources often estimate his net worth in excess of ten million dollars, though Vermeeren seldom confirms such things. For an actor emerging into broader cultural relevance, financial independence is not merely advantageous—it is strategic. It allows him to choose the projects he wants rather than the ones he needs.

So what now? The simplest answer—momentum. Hollywood has a long history of rewarding actors who refuse to fit clean templates. The market has become global and platform-based; versatility matters more than conformity. Streaming audiences are multilingual, genre-fluid, and delighted by actors who can jump from Western to thriller to documentary to martial arts without losing credibility. Vermeeren seems engineered for this era.

There is also the unspoken narrative factor. The industry—jaded as it may be—loves a good story. A boy from Canada who skipped class to sneak onto film sets. A teenager who learned how cameras work from ten feet away. A young stunt performer who rode horses in Westerns. A producer who distributed content in more than two dozen languages. A host who entertained audiences on another continent. An actor who won awards without first winning fame. And a man who, in his forties, appears to be accelerating, not coasting.

For now, the only certainty is motion. The calls have gotten bigger. The films more ambitious. The festival invites more frequent. And the attention—both fan and industry—more intense. Whatever the next chapter looks like, Douglas Vermeeren seems positioned not merely to participate in Hollywood’s evolving landscape, but to help shape it.

If the first half of his career was about proximity—getting close to sets, close to stars, close to opportunity—the second half appears to be about possession. Not being near the action, but becoming it. And in an industry built on transformation, there may be no better signal that a star has truly arrived than that.